Alvin Ing: Tales of a Theatrical Trailblazer

Alvin Ing (Photo: Lia Chang)

Musical theatre is a relatively young art form. With no real beginning, it was born out of a mixture of vaudeville, operetta, burlesque, and minstrelsy, creating one of the only American artforms (at least in its inception). As the art form has evolved, so has the makeup of its performers.

Alvin Ing is one such performer who pushed open the door for so many to follow. With a crystalline tenor and natural grace, he fought headfirst against racial discrimination, becoming a legend to those who have had the honor of knowing him.

Last month, I had the honor of speaking with Mr. Ing about his career, his legacy, and his hopes for the future. The following has been condensed and edited for clarity.

~~

MH: Let’s start at the very beginning

AI: I was born in Honolulu, and I'm a fourth-generation American; my grandparents on my mother’s side were both born in Honolulu. So growing up, you know, you want to be “American”. I had been to college and I had been in the army, in Schofield Barracks, which is in Honolulu. I was rather old when I finally got to New York City -- I didn’t get there until I was 25. I studied Music. I thought I was going to be a music teacher because in those days that’s all I could aspire to. I never thought I would be in show business. It never entered my mind. Because, you know, we’re a little island in the middle of the Pacific, and I had no aspirations because I thought it was very unrealistic of me to have those aspirations.

MH: Were your parents involved in music at all, or was this something you just had a natural affinity for?

AI: When I was a kid I loved to sing, I had a very high voice, and the first song I learned was O Holy Night. My aunt taught it to me when I was a little kid. And then I was in the church choir; first I was in the junior choir, and when I got older I was in the senior choir. And then I got to the University of Hawai‘i, for the first year I didn’t know what I wanted to do, but as some of my classmates went into music, that persuaded me that maybe I could do it too. So I then majored in Music Education.

MH: What age were you aiming to teach?

AI: I didn’t know at that time. I just thought I would be a music teacher. Whether it was elementary or high school -- but I never thought I would teach at the college level, because in those days, that was too far above me. I never thought I’d be able to do that. When I went to New York, I got my master’s in Music Education at Columbia.

MH: What was the moment where you thought, “Maybe I want to do performing rather than teaching”?

AI: Oh, that’s a whole different story. When I lived in Honolulu, I was in several musicals as an amateur. I was in a show that was written by Bob Magoon, who was one-fourth Chinese and three-quarters Caucasian. He was a composer and a playwright, and so he wrote several shows in Honolulu that I was in. When I got to New York City, I happened to see him in Times Square one day, and he had come to New York to try to get one of his plays on Broadway. He asked me to walk with him to the agent’s office so we could talk.

When we got to the agent’s office, he asked me what I was going to do. I told him I was going to go to Columbia in the fall. He asked me to sing, so I sang for him. A couple of weeks later, I happened to see him on the street. He lived on the corner of 57th and 7th Avenue, and he was waiting for a cab, we stopped to say hello, and out of the blue he asked me if I was interested in auditioning as a replacement for summer stock. And I said, “what’s summer stock?”

(Summer stock is an American theatrical tradition where regional companies stage productions in the summer using stock scenery and costumes they have on hand. These productions are often the springboard for performers that are early in their careers, serving as a way to meet other theatremakers, and potentially join a professional union.)

AI: He explained it to me, and I said to him, “let me think about it tonight and I’ll call you in the morning.” Well, this is where -- I believe that we all are psychic, up to a point. That night, I couldn’t sleep. I knew my life was going to change. I called him the next morning, he told me to go to Camden, New Jersey, and audition for Salvatore Dell’Isola, who was the original conductor of South Pacific, who was doing the show in summer stock. So I took the train to Camden, they picked me up, I auditioned for Dell’Isola, he accepted me, I took the train back, packed my bags, and I was in show business. That’s how it happened.

MH: You were in the ensemble, correct?

AI: Yes, I was. I was in the chorus, and it was a whole different world to me. The other kids in the chorus told me how to look in the trade papers to look for auditions and so forth, and eventually, I was able to get into a professional choir in New York City and worked a whole year, and got very good pay, in those days. Then the next summer I did a whole summer in Toronto and Buffalo. There were two tents owned by the same person. We did a show in one tent, and then you moved to the other tent and did the same show. In the meantime, we were rehearsing for another show. So we did Annie Get Your Gun, Song of Norway, and Oklahoma. So I was in the chorus.

MH: Was this around the time that you were also trying to get an audition for The King and I?

AI: No, no. This was much before. I was in the professional choir, I sang professionally in churches to earn a living. And so that happened for a couple of years, and when I thought I would try to get out of the chorus, the problems began. Because in those days, they didn’t cast any Asians in The King and I except for some of the kids, and some of the dancers. But all the main characters -- the leading men, leading ladies, they were all Caucasian. And so, I was not able to do Lun Tha, who sings “I Have Dreamed” and “We Kiss In A Shadow.” For many years, I could not get that role, until finally, I auditioned for a director who happened to be part Asian, and that’s how I got my first King and I.

MH: Do you remember the name of that director?

AI: Mara. That opened doors for me, and I was then able to do The King and I in several other theatres. Then in 1958, they announced the auditions for Flower Drum Song, and of course, I went to the audition, but even for that particular show, what they were looking for was not someone who looked that Asian -- they were looking for someone who looked more Caucasian. So they hired Ed Kenney from Honolulu, who was part white and part Hawaiian, but after he got the job he said he was part Chinese -- I never believed him. But he was tall, good-looking, and he sang very well, so he got the role, and eventually I got to be the understudy for Wang Ta on the national tour. That was in 1960. I toured with the national company, but unfortunately never got to go on for the role, for a whole year.

MH: The culture has definitely changed -- people never used to call out unless they were on their deathbed.

AI: Never. It was very frustrating. Anyway, Ed Kenney’s understudy got the role on the national tour, and he was part Asian and part white. So he did get the job, but he couldn't sing very well, and I don’t think he was a very good actor. But because he was Ed’s understudy, he got the role, and he would not let me go on even though there were times when he couldn’t sing, because he knew I could sing better than he. That was very frustrating. But eventually, after the national tour, I was able to do it in summer stock, and I have the dubious honor of having done more Flower Drum productions than any other actor.

MH: It is hard to determine the exact number of productions, but you’re definitely in the double digits, including the tour and the 2002 revival with Lea Salonga.

AI: I was happy to be in that revival, even though I played Uncle Chin -- I was older by then, and I was in an older role. The song they gave me was a song that was originally sung by Keye Luke, who played the father in the original production of Flower Drum Song. Unfortunately for Keye, when they got to Broadway, they took the song out of the show, so it was never sung. I actually premiered the song, “My Best Love” on Broadway.

MH: As far as I know, you are the only performer to premiere a song by Rodgers and Hammerstein and a song by Stephen Sondheim.

AI: Yes! I premiered “Chrysanthemum Tea” that Stephen actually wrote for me. Originally, it was a different number, but one day we were in D.C., the stage managers told me to go and meet Stephen in his apartment, so I did, and he said to me, “we’re changing the number, and this is what you have to sing.” He played for me -- and you know, I can’t find that damn CD, because I recorded it, and I can’t seem to find it anymore.

MH: A treasure!

AI: He played the song for me, and at the time I said to myself, “well, this is not very interesting melodically, because it goes on and on.” Do you know the song?

MH: Oh yes, it’s one of my favorites. It’s deeply hypnotic.

AI: It’s got four verses! So I thought, “oh my God, I don’t know if I like this song, but it was given to me.” And of course, after I learned it I realized the purpose of it and where it was going, and then, of course, I loved it.

MH: Did you have any tricks to keep all of the verses straight, since it’s so repetitive?

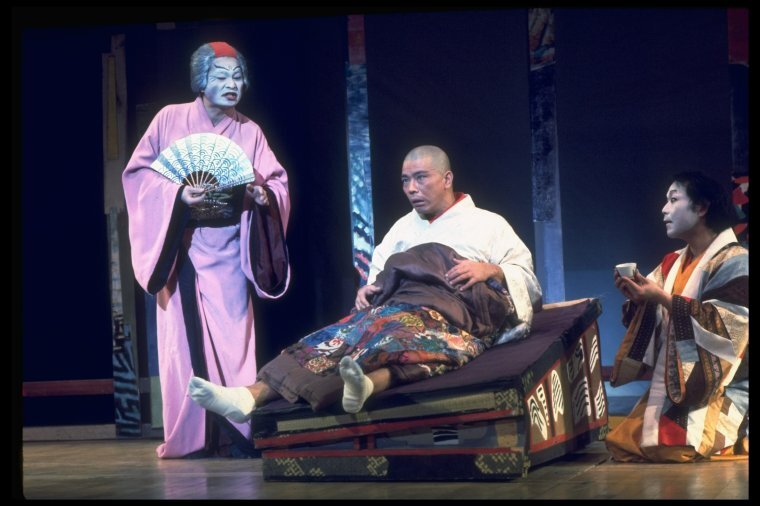

AI: In D.C., I had to learn it in four or five days, which was a nightmare. I couldn’t sleep. I had learned it up to the fourth verse and I wrote the fourth verse down on a piece of paper and I put it on the pallet that Mako was lying on, and the night that I went up on the fourth verse, his head was on the paper and I couldn’t see it. So I just kept fanning myself until it came to the chorus. “Have some tea, my Lord”.

Alvin Ing and Mako in “Pacific Overtures”

MH: Can you tell me a bit of what opening night of Pacific Overtures was like? Because that was your Broadway debut, correct?

AI: Yes. It was probably the most exciting night in my career, and never to be forgotten. After that, we had a reception, and I bought a Japanese kimono and geta. It was so fun - I still have the kimono.

MH: I’m sure it was beautiful. What color was it?

AI: Kind of brownish. I wore it again to the opening of the 2004 revival.

MH: What was your audition for Pacific Overtures like?

AI: I sang “Right As The Rain.” I still have the arrangement. I think I did three auditions. I was one of...it sounds immodest, but I was one of the better singers in the cast. A lot of them were not singers, they were actors. But the best singer in the cast was Mark Hsu Syers.

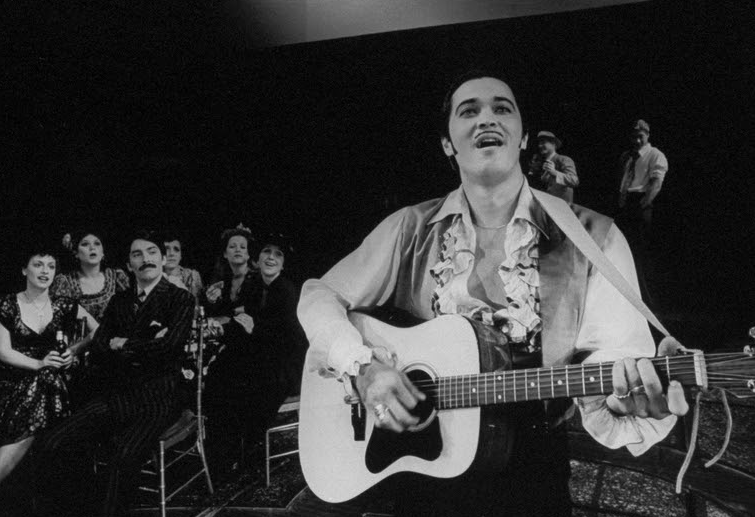

He was the most talented person in the cast in terms of music. He had a terrific voice with an enormous range. He could sing almost as high as I could and sing much lower. So he had a terrific voice and he was a very good musician and he played the guitar very well. Unfortunately, he was also into grass. I never reported him, but he was high many times in the show, but he was able to perform anyway. Of course, it was a big no-no in those days. Still is. But I liked him a lot. We became friends, and unfortunately he passed away very young.

MH: Oh, very young. In the crash.

AI: It’s very sad, because he died so young and he was so talented.

(Mark Hsu Syers was suddenly killed in a head on car crash on a rainy night in 1983, at the age of 30. In addition to his work on Pacific Overtures, he was known for his roles as King Herod in Jesus Christ Superstar, and Magaldi in Evita, pictured above)

MH: Pacific Overtures was one of, if not the first productions to require that their company be made up entirely of Asian or Asian-American performers.

AI: Yes, it was the first. However, Jimmy Dybas was the only non-Asian in the cast, and he lied to get into the show. I didn’t realize it because I was so naive, but the other members of the cast who were older and more experienced realized that he had lied, and so nobody wanted to room with him, so they made me room with him. I still remember that in D.C., after the show ended -- an actor he knew came to congratulate him, and the first thing out of his mouth was, “how did you get into this show?” I didn’t say anything, I just took my makeup off and that’s when I realized that he was not Asian. He was not embarrassed; when we opened the revival he came to the opening and then to the reunion. He won the Legacy Robe because he was the longest working person in the cast. He was not embarrassed about what he had done. The bad thing about him being in the show was that he put some Asian out of work.

Alvin Ing in “Pacific Overtures”

MH: And it was certainly hard enough for you at that point -- you essentially had The King and I, Flower Drum Song, and Pacific Overtures, right?

AI: Yes, exactly. So from that point of view, I did lose a little respect for him, because he didn’t seem to have any qualms about it or remorse, he never apologized.

MH: Did you have any difficulty finding work after Pacific Overtures?

AI: Oh yes. But you know, I had been on five national tours, and I sang in churches all my life in New York, that was a way of earning some money to keep me alive, and fortunately I had an apartment on the East side, and it cost me $49 a month in those days. I was able to survive because I paid very little rent, and all churches -- in those days -- were professional. We all got paid in churches. I was in several professional choirs, so that also kept me alive, and I worked in Bloomingdales’ at Christmas, as did many other actors.

What is sad during this pandemic is that chorus people couldn’t do that anymore -- they couldn’t be waiters, they couldn’t be dressers, they couldn’t be salespersons, because all these places have closed up for a while.

MH: Survival jobs are gone too.

AI: I’m sure it is really, really hard for all the chorus people during this pandemic.

MH: At what point did you get involved with East West Players?

AI: When I decided to come to Los Angeles in 1977. I was at the Manhattan Plaza, and in those days, they were very strict, so when I was in Los Angeles, working at some point and looking for work, and so they kept harassing me about not being there, and eventually I decided to leave. I loved living in New York, but I wasn’t working, and so I decided to go to Los Angeles under the persuasion of Guy Lee, who was an agent in Los Angeles, and he was Soon-Tek Oh’s agent, and he persuaded me to move to Los Angeles and I did, and I was able to work in lots of TV shows. So that kept me alive, and eventually, I got to enjoy Los Angeles.

It took me many years to get used to Los Angeles. In New York, I was out every night. There were so many things to do in New York that you couldn’t do in Los Angeles. I would go to a concert, the ballet, the opera, the shows. And when I came to Los Angeles, there were very few shows to go to and certainly very little opera. Later on, they opened an opera company that was directed by Plácido Domingo, but that was after I had arrived. Now I’m used to it, I have a car, I have my condo, and so it’s much easier to live here than in New York.

MH: And so, at East West, you reprised your role there as the Shogun’s Mother for the first time, right?

AI: Yeah, I did it twice. They did several revivals of it, and I would do the same role each time. I did several shows there, including Follies, Cabaret, Company, some originals, and others.

MH: And was this while Mako was still associated with the company?

AI: At first, he was. And then he left, Nobu McCarthy became the director of the company, and then eventually she left and Tim Dang took over. It was during Tim Dang’s tenure that I finally stopped working, because I was too old for most of the shows. I was very loyal to East West for many years. We got very little money, but somehow, Tim Dang kept it going, and it’s still running. When this pandemic is over, I’m sure they will be working again.

MH: Can you tell me a bit about going back out on tour with Flower Drum Song in 2004?

AI: Yuka [Takara] toured the revival of Flower Drum Song with me. It was a short tour, we went to Houston, Dallas, Seattle -- I think about three, four months. Yuka played the lead, and she was quite wonderful.

MH: She’s a wonderful woman.

AI: Very wonderful. First of all, it was sort of her life, because she does come from Okinawa, and fortunately, she is bilingual -- otherwise, she probably wouldn’t have been able to get a job. She did terrific. I always wished for her that they would revive the show for her to do it, but they never did it again.

MH: The relationship between the two of you, at least of what’s public online, is so sweet. I love the video that you did together with “Dynamite” by BTS.

AI: Oh, you got it? How did you get it?

MH: I found it on YouTube!

AI: Oh, that’s funny! Yeah, Yuka lived with me for almost ten years.

MH: Oh, wow!

AI: After Flower Drum Song, after Pacific Overtures, she wanted to come and try LA. So, you know, I have a condo, I have a guest bedroom, guest bathroom, so I invited her to live with me for almost ten years. She would do jobs elsewhere, go back to Okinawa, Tokyo, and Korea, and she didn’t move out until she got married. That’s how close we are. She’s like my daughter. I consider her like my daughter. She’s been very good to me.

MH: You’ve had a really fascinating career renaissance over the last ten years, with the workshops of Honeymoon in Vegas, your solo album, auditioning for The X Factor -- it’s been really interesting to see all that you’ve been doing.

AI: I still like to perform and I still like to sing. Fortunately, I can still sing. And I have been to Okinawa at least ten times with Yuka, and because she is from there she has connections and we were able to do concerts together. So that was very satisfying to me, and I loved being able to go to Okinawa and Tokyo, and Korea to do these little concerts.

MH: I love the album that you put out last year, “Broadway Is Still Calling.”

AI: Oh, thank you, thank you.

MH: Can you tell me a bit about your decision to come out in 2016 in your cabaret act?

AI: Lainie Sakakura, who put my act together, she convinced me that I was old enough not to be so reticent about it. In a way, it was very satisfying, but I really would like to do it for the gay community. I haven’t had a chance to do it, of course, because of the pandemic. But I have been in touch with certain gay producers, and when this pandemic is over, maybe I can still do it with them. That’s what I'm hoping. Because, number one, I’m old, I’m Asian, and I’m gay, so maybe it would be -- I don’t know, an inspiration for other people.

MH: You’re an elder! You’re someone that we can look to as a person who, in the face of a huge amount of adversity, lived life to the fullest and, as far as I know, seems to have come out the other side pretty happy.

AI: Yeah, I have been. You know what I tell my old friends and classmates when I go home to Honolulu? I say “the difference between your life and mine was that I had fun.” That’s the truth!. Can you imagine working in an office, eight hours a day for years and years? I was on the road, traveling all through the states in my national tours, and I worked in Vegas three times. I did Mame with Susan Hayward, I did Flower Drum Song twice at the Thunderbird, and I did The World of Suzie Wong at the Riviera -- that was the first show I did, in 1960. The World of Suzie Wong was the first non-musical to open in Vegas.

MH: I’m sure that must have been amazing.

AI: It was fun. In those days, we did two shows -- one at eight, one at twelve. Each show was only 90 minutes long. So what do you do between shows? You gamble, you eat. So I was on the blackjack table all the time between shows.

MH: Did you have lucky hands?

AI: I wasn’t very lucky. But in the end, I only lost maybe three or four hundred dollars, so when you consider how long I was there it wasn’t bad. I loved working with Susan Hayward, even though she kept very much to herself. She was very weak, and between shows, she went into her dressing room and didn’t come out until the second show. We didn’t have very much contact, but on the other hand, I was still working with Susan Hayward! I thought she was pretty good in the role.

MH: In light of everything that has been happening in the past year, in terms of acts of hatred against the Asian-American community -- do you have anything you’d like to say?

AI: I believe so much of this resentment against Asians was caused by Trump calling it“the China virus”. It has impacted all of the Asians -- not only the Chinese because Caucasians can’t tell the difference between Chinese, Japanese, Thai, and Korean. All of the Asian-American population is impacted by it, and it’s such a shame. I mean, you know, they’ve been attacking older Chinese women, for instance. What kind of country are we in, you know? It’s something unbelievable. I never thought this would happen again after the Japanese were interned during the war. I thought that was a lesson to be learned, but obviously, we did not -- America is still very racist. I don’t know how it can be resolved, because, you know, there are so many Trump supporters in our country. It’s amazing. Don’t you find it strange that so many people are still supporting him?

MH: This sort of hatred that is bone-deep in some people -- as little sense as it makes -- is something we have to reckon with.

AI: Right. I didn’t realize there were so many white supremacists in our country until this happened. I mean, it was frightening. It made me be wary about walking around in crowds, even going to the supermarket, because it has happened at supermarkets and on the street. So it’s disheartening -- it really is disheartening. At my age, I don’t want to be fearful when I go out. We do have to be on our guard, and I’ve had some very supportive comments from friends who are always looking after me.

MH: At the BC/EFA celebration of Flower Drum Song turning 60, when you came out with about a dozen other performers from various productions -- can you tell me a bit about what that moment was like?

AI: It was very moving, and I have to say that when I started to sing I began to cry. Thinking about it makes me teary also because Flower Drum Song was my whole life at one point. It was the only show I could be in. I am very grateful to it because it supported me for many years, and so at the reunion, it all came back to me, and I became very emotional. Because I owe a lot to Flower Drum Song -- whether people liked it or not, it gave me a livelihood that I wouldn’t have had otherwise.

MH: It was that first step.

AI: If it hadn’t been for Flower Drum Song, I probably would have quit the business. There was hardly any work for an Asian then. So I’m very grateful to Flower Drum Song and to the revival because it helped me a lot in my life. They gave me a plaque, that was Baayork Lee’s idea. What is wonderful is that my friends from Flower Drum Song and Pacific Overtures are the ones that have lasted all these years.

They were the only shows to do, they were the only jobs we could get at that time - we were a family. That will be my legacy. Flower Drum Song and Pacific Overtures, and I’m very grateful to both shows.